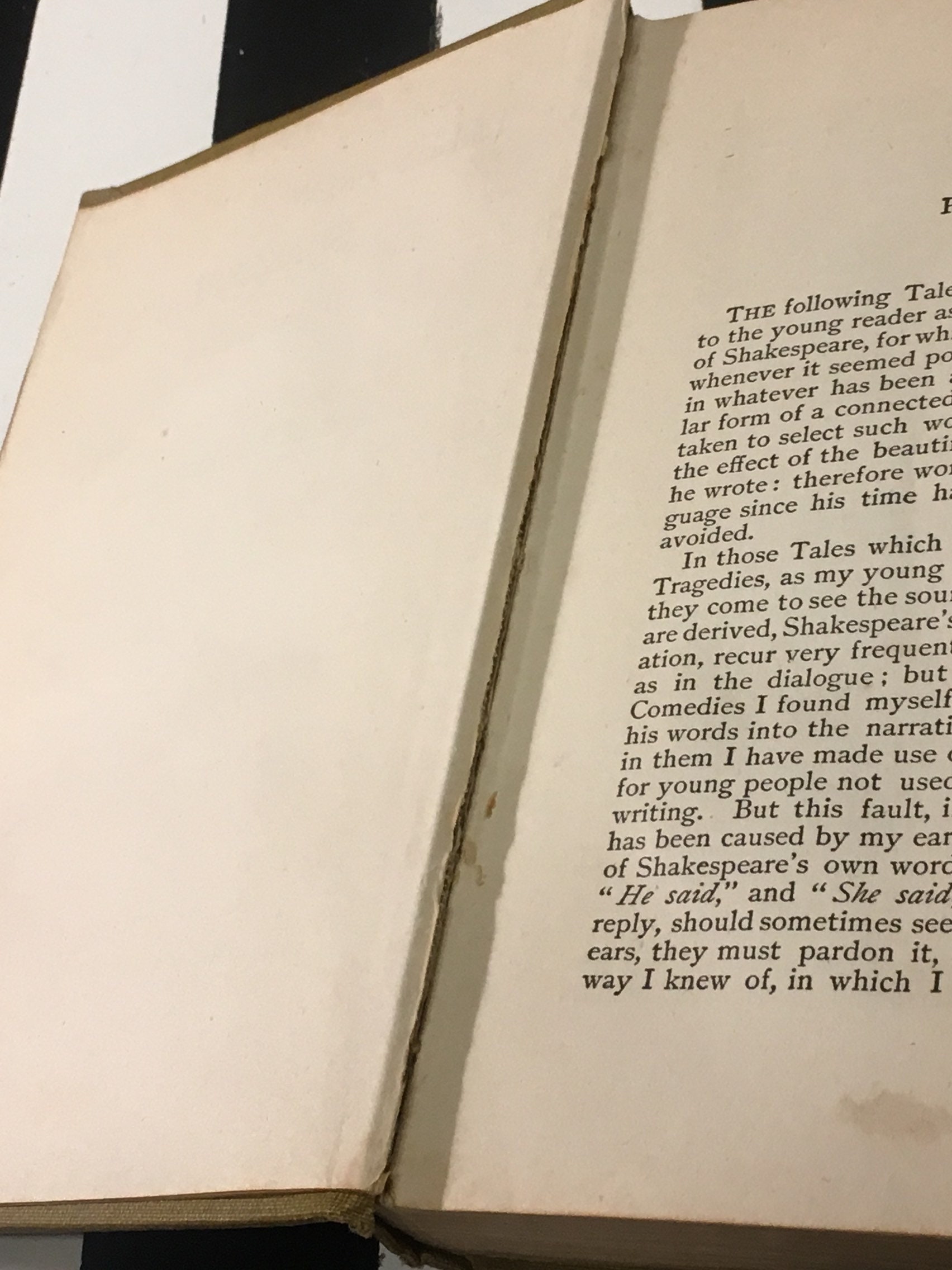

Previous studies of Tales from Shakespeare have focused on Charles's dislike of heavily didactic children's literature and the ways in which the Tales oppose this didactic tradition.4 While reintroducing imaginative fiction to children may have been Charles's aim, it was not Mary's main goal.

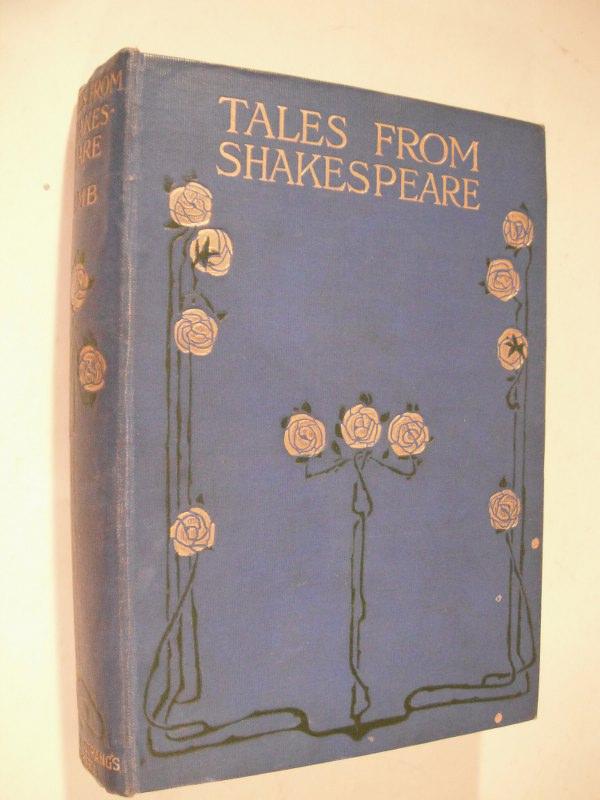

Elements of gender were thus purposely written into the text of the Lambs' Tales, elements which previous critics have seemingly refused to see.3 The "feminization" of Shakespeare took a variety of forms, for unadulterated Shakespeare was seen as improper for a delicate female mind (hence the publication of the Reverend Bowdler's popular Family Shakespeare within a decade of Tales from Shakespeare).2 Where boys might expect to learn courage from Shakespeare's "manly book," girls had to be presented with a version of the plays which would encourage development of feminine graces-modesty, patience, and gentleness. Although the book was Mary's idea and she was its primary writer, the Tales were published under Charles's name well into the twentieth century.1 By ignoring Mary we overlook not only her contribution to Tales from Shakespeare, but, even more important, the ways in which she deliberately directed this project toward a female audience.

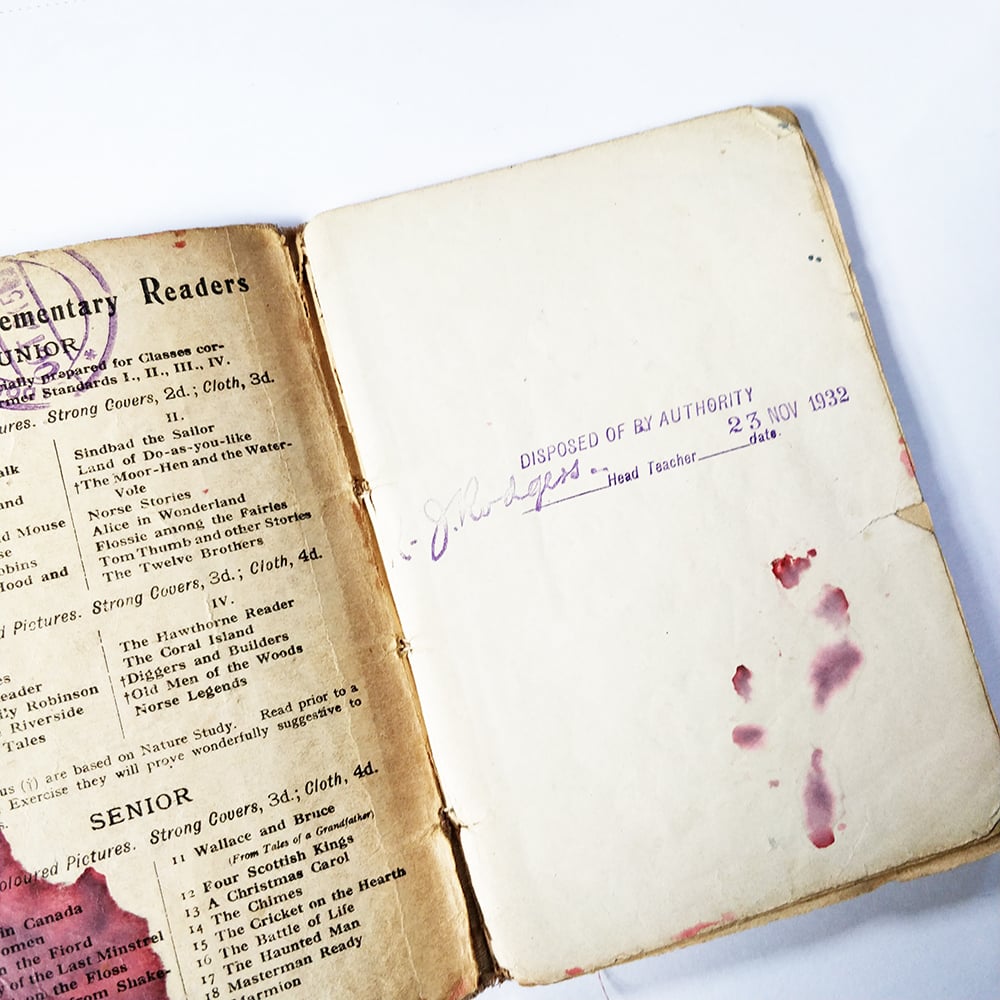

Mary began the project and wrote fourteen of the twenty tales (the comedies and romances), while Charles contributed versions of six tragedies. As a result, her role in the composition of Tales from Shakespeare has been almost completely overlooked. Mary's family and friends, it seems, were kinder to her than literary history has been today she is remembered almost exclusively as the perpetrator of a lurid matricide. Mary recovered and spent the remainder of her long life looking after her brother Charles and writing children's books, including the popular Tales from Shakespeare (1807). On September 21, 1796, in a fit of madness, Mary Lamb picked up a knife and fatally stabbed her mother.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)